My research paper looked into Early Modern Anti-Semitism and how it affected literary works of the Early Modern period. Specifically, The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare and The Jew of Malta by Christopher Marlowe were considered with respect to the characters Shylock and Barabas. Through my various research excursions, I found that although Shylock and Barabas are both portrayed very negatively in their respective plays, Barabas is more purely evil than Shylock. With this difference in mind, it is still important to understand that the Early Modern perception of the Jew was very negative and stereotypical and both characters reflect this negative image. The stereotype of the time included titles like usurer, child-sacrificer, Christ-killer, and Jew-Devil. Jews were also typically pictured with horns and poison. All of these stereotypes were supported or enhanced by contemporary Early Modern art.

Literary pieces like The Merchant of Venice and The Jew of Malta were huge successes because of the negative portrayal of their Jewish characters, even though it is likely that neither writer ever knew a Jew personally. Dr. Roderigo Lopez was brutally executed in 1594 for allegedly planning to poison Queen Elizabeth, and it was his previous Jewishness sealed his fate and “proved” his guilt. The sculpture, Moses carved by Michelangelo in 1515, portrays the great Biblical Jew with horns. The woodcut “Jew Poisoning a Well” completed in 1569 shows a Jew poisoning a well that the Devil is urinating into and there is also an image of a child on a cross. All of these art forms support the negative stereotyping of Jews in Early Modern Europe.

Such archetypes of the time helped to form the horrible characters of Shylock and Barabas. Both men claim to hate Christians and they go to extremes for money. Their behavior certainly seems to mark them as Jew-Devils and as such they become innately negative characters. They are acceptably illustrated this way, because such horrible Anti-Semitism was culturally acceptable in the Early Modern Period. Things like the Bible seemed to support it, and the judicial system provided its two cents with the hearing in the Roderigo Lopez case. The people cannot be blamed for their conditioning, but the suffering of the Jewish population in Europe at the time cannot be ignored.

Works Cited (all of these were used in my paper)

USED FOR PRESENTATION:

Biberman, Matthew. Masculinity, Anti-Semitism, and Early Modern English Literature: From the Satanic to the Effeminate Jew. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2004. Print.

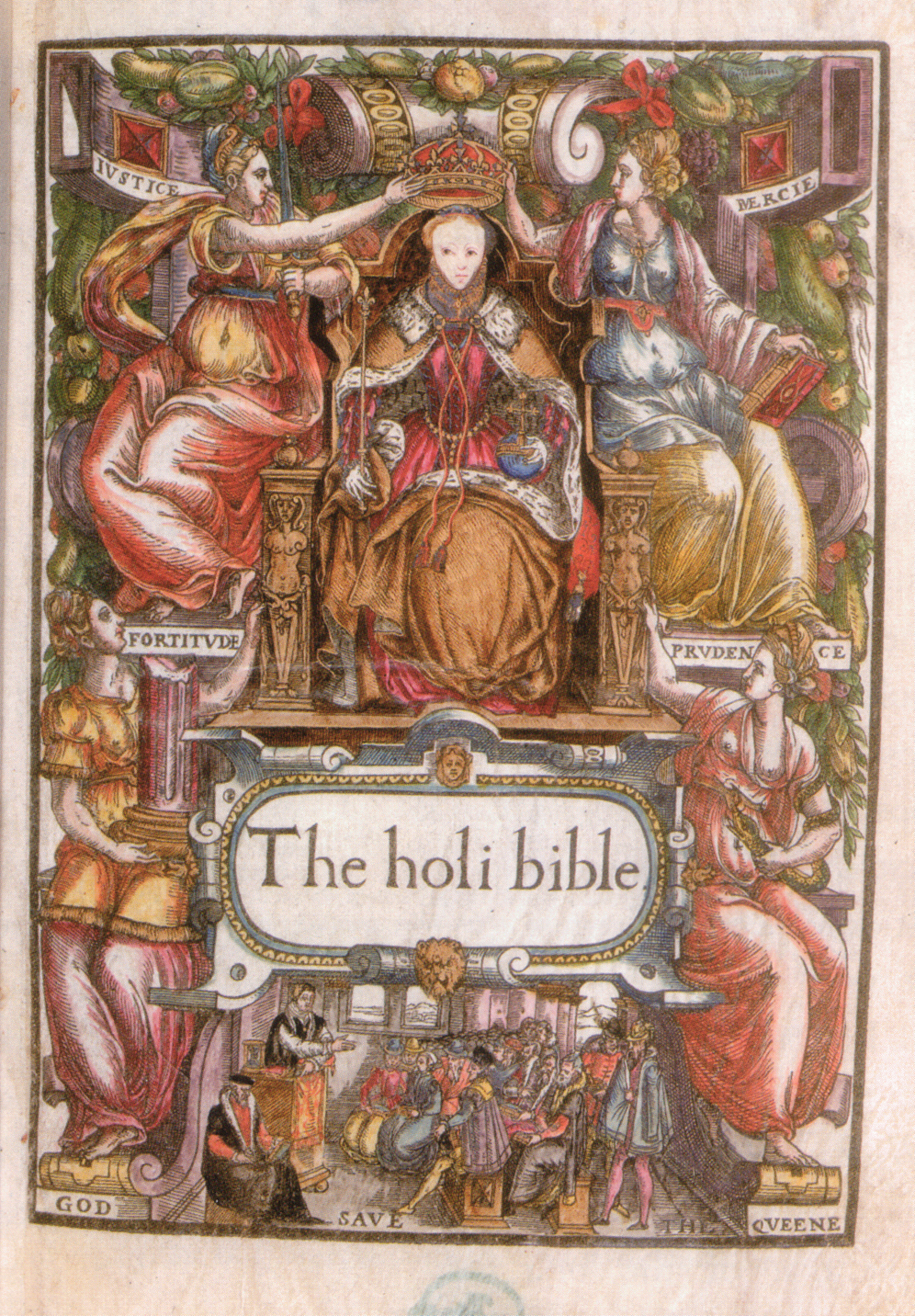

The Bishops Bible. Web.

Boaistuau, Pierre. “Jew Poisoning a Well.” Histoires Prodigieuses. 1569. (woodcut)

Kaplan, M. Lindsay. The Merchant of Venice: Texts and Contexts. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002. Print.

Marlowe, Christopher. The Jew of Malta and The Massacre at Paris. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers Inc., 1966. Print.

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. The Norton Shakespeare. 2nd Edition. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, Katharine Eisaman Maus. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2008. 1121-1175. Print.

SECONDARY (for those interested in further research):

Dessen, Alan C. “The Elizabethan Stage Jew and Christian Example: Gerontus, Barabas, and Shylock.” Modern Language Quarterly 35.3 (1974): 231-245. Web. 7 November 2009.

“The Edict of Expulsion: Enacted 1290.” Britain Express. Web. 16 November 2009.

Kamin, Ben. “Why Do Jews Have Horns?” Examiner.com. 30 January 2009. Web. 17 November 2009.

Katz, David S. “Dr. Lopez and Shylock.” Commentary 102 (1996). Web. 16 November 2009.

Michaelangelo. Moses. 1515. San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome.

Sanders, Lauren. Queen Elizabeth’s Dr. Roderigo Lopez versus Shakespeare’s Shylock: Similarities, Differences, and Their Influences on Elizabethan England. 2008. Web. 16 November 2009.

Shapiro, James. Shakespeare and the Jews. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. Print.

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Research Blog #5 - The Usury Bill

The Usury Bill was a much debated bill that prohibited usury under the reign of King Henry VIII. It was a compromise and compilation of many previous bills before it's time. It was eventually passed into law in 1571. It lays down specifics as to interest and it became illegal to charge interest in the name of God. This shows the amount of importance Englishmen placed on usury. It further emphasizes how bad it was that Shylock was deemed (and a self-acclaimed) usurer.

>Kaplan, M. Lindsay. The Merchant of Venice: Texts and Contexts. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002. Print.<

he kills her-he stabs the empress-he kills TITUS-he kills SATURNINUS-confusion follows

The title of this blog contains the stage directions found in Act V Scene 3 of Titus Andronicus within the space of nineteen lines. This is blood and guts madness. It is horribly fascinating. It is the dream of young America come true in Early Modern drama. America's youth loves gore and violence...and this is a stunning display of such. The lines of good and evil are so horribly blurred here that when "confusion follows" it only seems natural. The numbing effect of the brutality has the audience saying "this is kinda cool." How bizarre. The play starts off really dark and sad, and the killings have a horrible effect on the audience. However, as the play progresses everything seems to come unhinged and crazy. The killings are all over the place and for no rational reason. Everyone ends up dead, but I feel like it is fitting. I am in no way upset by how the play ends with dead bodies everywhere. It is just ridiculous and over the top and too much. But REALLY entertaining. I do like this Shakespeare. The shift and numbing effect really makes the play seem like one of the SCARY MOVIES or something like a farce. Titus was an interesting character and I am not sure how his hero thing ended up working out for him, but the play really has a cool way of making you not sure who to root for and the fun is that it doesnt really matter in the end. Perhaps this is the point.

Monday, November 23, 2009

titus...

So far this play presents an interesting plot-line. It is a little complicated and I definitely had to read through it a couple times before I really understood exactly what was happening. I am impressed with all the action that is happening so far. Already I have seen four dead bodies! I know it is going to get really good when there is so much gore to start off with. I feel like I can't really make up my mind about any of the characters yet. I think Titus is a good guy even though he killed his own son...but that was an extenuating circumstance. I guess. I think I am definitely skeptical about Saturninus and Bassianus. They just seem like really sketchy characters to me. Tamora is awesome. She is a fascinating female character - even for Shakespeare. I like her so far. We will see how my opinions progress as I move along throughout the play. Interesting first act though...for sure!

Thursday, November 19, 2009

Research Blog # 4 - The Bishops BIble

This is the edition of the Bible that Shakespeare would have been familiar with. It was an English translation of the Bible approved by the Church of England in 1568 and it was "extensively revised" in 1572. Later it was used as the base for the translation of the King James Version in 1611. It was developed because the people of the Anglican Church were displeased with the Geneva Bible and they felt that the Great Bible "was severely deficient." It was not meant to be a domestic bible, but one that was for readings at a church service. The first edition was really big and contained over 1oo full-page illustrations.

>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bishops%27_Bible

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Research Blog #3 - "Jew Poisoning a Well"

This woodcut is from Pierre Boaistuau's Histoires Prodigieuses. It is dated around 1569 and depicts a Jewish man poisoning a well that the Devil is urinating into and in the background there is a child hanging on a cross. All these images support Anti-Semitic beliefs about Jews in the Early Modern period and each part represents a different stereotype of the Jew. There is the stereotype about Jews being in a relationship with the Devil, a common fear was that Jews were very dexterous with poisons, and there was another morbid belief that Jews sacrificed and ate children. While this is all very disturbing, it provides insight about the perception of Jews in Early Modern England.

"Chop off his head"..."Off with his head"

Richard gets more and more decapitation-happy as the play progresses. As soon as he started talking about killing the two boys for no real reason, I began to feel less sympathy for the morbidly intriguing social climber. I feel like his evilness is getting out of control and it is really bizarre to see how he continues to fool people even though he has killed so many people and said so many bald-faced lies. A prime example is in Act IV scene 4, when Richard is tries to (and succeeds in) convincing Queen Elizabeth that he should be able to marry her daughter, Elizabeth. Queen Elizabeth already knows what horrors Richard is capable of! How can she be so impressionable? Richard is clearly a first class smooth talker. His confidence is unbelievable and fascinating, much like the rest of his qualities. In short, as the play goes on, Richard really begins to fulfill his monstrous descriptions and expectations. His animal descriptions, quick temper, lack of conscience, and ability to manipulate people with his words is astonishing and I would easily attribute it all to his monstrosity. I am still intrigued by Richard and the psychology of his character, but I am less sympathetic to him now. I think he deserves no sympathy.

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Research Blog #2 - Jew of Malta

The Jew of Malta is a play written by Christopher Marlowe in the year (probably) 1589. It is considered a very strong influence for Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice. It presents the Jew main character, Barabas, as a corrupt, money loving, villain. Early Modern Europeans had very strong prejudices against the Jewish people (even though there weren't any in England during the time thanks to the Edict of 1290). They perceived the Jew as being usurers and obsessed moneylenders in the economic world, and Christ-killers in the religious world. This play supports all kinds of negative ideas about Jews that were present in the time. There seem to be no true redeeming qualities about Barabas - he poisons an entire convent for Pete's sake! And there is not a positive alternative for him in the end. People in England at this time, ate stuff like this up. They loved it. What a reflection of a culture!

"and seem a saint when most i play the devil"

There is absolutely no denying that Richard is a nasty, twisted, vile, devil of a character. But somehow, he seems attractive to readers...how is this so? We must be attracted by the honesty and the way he takes us into his confidence. To me it just seems wrong in retrospect. However, I do feel like this is a feeling that lasts throughout the play for me so far. Everything is so disturbing and crazy the whole time that I almost don't feel bad for anyone. Well except Clarence. He was just a nice guy. But Lady Anne was just too gullible or sadistic or weak or something. All the rest of the women in the play make up a very strange and interesting part of the play - I can't really figure them out yet. Queen Margaret might be my favorite character. She is really nuts! The parallels between Lady Anne and Queen Margaret come in their curses and witty exchanges with Richard. I find this play partially disturbing and disturbingly interesting. It is one of those things that is just so awful that you cannot look away. I can't wait to see how the story progresses.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Love Questions and Breaking the Rules

I ended up really enjoying Twelfth Night all the way through. I found the gender role questions really interesting and the whole play was really funny. The pairings in the end were so ridiculous and quick that they did not seem completely realistic, but I suppose the entirety of the play was pursued in that light. My feelings were not hurt at all by the dismissal of Malvolio, because he was such a kill-joy anyway (and how ironic that he ended up having some of the funniest scenes); I did however, feel a little bad about Antonio. In my experience with Shakespeare, the Antonios never really get the best deal. I mean they usually come out OK but they are not ever the real winners (note Merchant of Venice and The Tempest). Sir Andrew was just kind of a joke ("a boob" in Dr. Staub's fitting words) the whole time and it didn't really bother me that he was forgotten in the end either. I did find the duel/letter confusion with Viola/Cesario pretty funny and an interesting commentary on the innate-ness of masculinity and femininity. Shakespeare's ideas about homosexual love, and the easiness of the shift between male and female come through in a really interesting way at the end of the play. For example the Viola and Orsino plot makes an interesting turn and exit. Orsino still refers to his love as Cesario and Viola/Cesario is still in his man's clothing when they exit. This leaves the audience with a really interesting final image of love and homosexual (gasp!) love on the stage.

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

VIOLA-OLIVIA-M.O.A.I

So far I love the good humor found in this play! It is a welcomed relief from the underlying tensions of the other comedies we have read so far. Not that this one is lacking innuendo and social commentary, but it is done in a much less offensive way for everyone involved (except Malvolio haha). We have been discussing in class the crazy gender role portrayal that this play deals with in humor. Of course Viola is a natural point of discussion: the actor that played her is a man, who is playing Viola (a woman), who dresses up in the play as a man (Cesario). Good Lord that is confusing! Then of course there is the twisted love triangle between Viola/Cesario - Olivia- and Orsino. And then there is the "gentlemanly" love between Antonio and Sebastian! If you have a little bit of a headache to go with that madness, you are not alone. But what makes it all bearable is that it is FUNNY. It is very funny and the crazy gender madness only increases the humor. I think it is fascinating that Shakespeare makes a potentially touchy subject an object of humor and easy acceptance. Shakespeare makes the idea of gender something that seems less permanent and more suceptible to change. This concept is pretty revolutionary for his time and even for ours...

Monday, November 2, 2009

Research Blog: Primary Source 1

This is an image of Michaelangelo's David. It was carved from marble in 1515, it is located in San Pietro (Saint Peter) in Rome. I am interested in this because it provides a physical representation of a strong Jewish stereotype of the Early Modern Period: horns. It was a common belief that Jews were associated with the devil, but that is not where this stereotype came from. It came from the Bible: Exodus 34:29-35 tells the story of when Moses descended from Mt. Sinai. It says "the skin of his face shone" the Hebrew for "sun on his face" is qaran which can also translate to mean horns. I think it is interesting that such a well known artist would choose to incorporate the horns in his sculpture of Moses. This shows the heavy influence of Jewish stereotypes that are present during the period.

>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_(Michelangelo)

Monday, October 26, 2009

Shifts in Venus?

OK first of all. I need to clarify...during my initial reading and response, I over-interpreted and thought that Venus convinced Adonis to have sex with her. CLEARLY she did not. I apologize for this mistake; I was considering the kissing to be more than just kissing :-)

It was interesting to view the shift that seemingly occurs in this poem. It is almost as if Venus moves from a lover to a mother. This is very strange, but it makes the ending a little more serious than the flippant, humorous beginning. One of the biggest themes in the poem is the changing sexuality of Venus and what it means, exactly.

At times she seems like she takes on a more masculine role (plucking Adonis off his horse) and having more strength and her sexuality seems like a voracious monster out for sexual feeding. It is complicated to try to put an exact label on what her actions mean for society. It is confusing because it is difficult to tell whether she is supposed to be a masculine shrew, or if the feminine label is stretched and skewed because she is a goddess. Her overtly sexual tendencies at the beginning of the poem are comical and vastly contrast with Adonis who seems very under sexed.

He is very youthful and boyish to the point of femininity. These contrasts are shown with the white and red descriptions. It almost seems more natural then, when in the second half of the poem, Venus speaks of him like a child. His death is made all the more sad because his youthful childishness was lost and he was robbed of the chance of growing to be a man -- if he were destined to be such.

The poetry was so beautiful and I really enjoyed this poem. It was an excellent read, and provoked deeper thought about sexuality. Especially female sexuality.

It was interesting to view the shift that seemingly occurs in this poem. It is almost as if Venus moves from a lover to a mother. This is very strange, but it makes the ending a little more serious than the flippant, humorous beginning. One of the biggest themes in the poem is the changing sexuality of Venus and what it means, exactly.

At times she seems like she takes on a more masculine role (plucking Adonis off his horse) and having more strength and her sexuality seems like a voracious monster out for sexual feeding. It is complicated to try to put an exact label on what her actions mean for society. It is confusing because it is difficult to tell whether she is supposed to be a masculine shrew, or if the feminine label is stretched and skewed because she is a goddess. Her overtly sexual tendencies at the beginning of the poem are comical and vastly contrast with Adonis who seems very under sexed.

He is very youthful and boyish to the point of femininity. These contrasts are shown with the white and red descriptions. It almost seems more natural then, when in the second half of the poem, Venus speaks of him like a child. His death is made all the more sad because his youthful childishness was lost and he was robbed of the chance of growing to be a man -- if he were destined to be such.

The poetry was so beautiful and I really enjoyed this poem. It was an excellent read, and provoked deeper thought about sexuality. Especially female sexuality.

Monday, October 19, 2009

initial impressions of "Venus and Adonis"

So far I like this work a lot. It was a little difficult for me to concentrate at first because I would get caught up in the poetry and stop paying attention to the meaning of the words. Eventually I got the hang of it though. The similarities between this poem and "The Rape of Lucrece" were astonishing to me. All the talk of white and red, and the innocence of Adonis in comparison to the innocence and virtue of Lucrece were astonishingly similar, and I suppose you could say that Venus raped Adonis in a way by simply wearing him down. However, it was definitely less violent this way and they have intercourse twice which sounds consentual to me. Maybe I am not being objective enough. I could certainly see the masculine roles that Venus played with her strength and cunning as she is dominating the conversation and the scene. Voice seems to be a symbol of power in this work as is similar in other Shakespearean works we have read and Venus has most of the voice. It was funny, Venus' pleading language and pouting must have been very convincing because at points I kept thinking "Just do it Adonis, it won't be so awful - surely!" then I had to remind myself that Venus was supposed to be the powerful bad guy (I suppose) and that I should have been rooting for Adonis. I found it pretty amusing as a reader to get so involved. I think that made it really real for me, and more accessable. Altogether I have enjoyed it so far.

Sunday, October 11, 2009

"keeping safe Nerissa's ring" - that curious Act V

I am glad that I did not end up hating The Merchant of Venice. It is true that the Antisemitism acts as a huge turn off during the bulk of the play. However I liked the plot line that placed Portia in a strong place of real power. Portia proves herself in the brilliant turn around in the courtroom and puts Bassanio in his place. In my opinion, Bassanio deserves to be harangued by his wife - he is a shady character to begin with, and he did not prove a very loyal husband when put to the test (both by Portia, and out of his own mouth).

I thoroughly enjoyed watching him get told by his awesome wife. haha. And although Act V seems rather unnecessary, I liked the comic relief it provided with Bassanio and I am able to see how the audience would appreciate an ending with a man provided sex joke. This play was full of heavy material and even if the audience was able to laugh cruelly at Shylock the whole time, it was a somber moment to watch him walk off stage defeated and punished at the end of Act IV. No one wants a comedy to end so heavily. Watching Portia take control might have been comical but a little upsetting to a conventional patriarchal English audience of the time, so what better way to bring back the audience than to comfort them with masculine control in the form of a vagina joke?

huzzah.

I thoroughly enjoyed watching him get told by his awesome wife. haha. And although Act V seems rather unnecessary, I liked the comic relief it provided with Bassanio and I am able to see how the audience would appreciate an ending with a man provided sex joke. This play was full of heavy material and even if the audience was able to laugh cruelly at Shylock the whole time, it was a somber moment to watch him walk off stage defeated and punished at the end of Act IV. No one wants a comedy to end so heavily. Watching Portia take control might have been comical but a little upsetting to a conventional patriarchal English audience of the time, so what better way to bring back the audience than to comfort them with masculine control in the form of a vagina joke?

huzzah.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Struggling with Shylock...and all that talk about blood

I cannot seem to keep up with all these characters in Merchant of Venice. I still struggle with Shylock as a villain and try to give him a sympathetic ear as well (this proves difficult for me despite his poor treatment). He certainly plays on the fact that he is just as human as everyone else in his famed speech in Act III Scene 1 ("Hath not a Jew eyes?") but also justifies his thirst for revenge by claiming that it is human and any Christian would do the same. Surely Shakespeare meant for readers to think twice about the Jew question but at the same time he certainly plays up the negativity towards Judaism as was popular during his time.

Throughout the play blood acts as a common recurring theme. This is very interesting to me. It appears that blood is an idea that connects people in this play. Shylock and Jessica are linked (this may be unfortunate in Jessica's mind) because, being his daughter she is Shylock's "own flesh and blood" (Act III Scene 1). In the same act, Shylock links himself to Christians by finding the common ground with the question "if you prick us do we not bleed?" The Moroccan prince claims to be as good a suitor as anyone else by offering to "prove whose blood is reddest" (Act II Scene 1). In Act I Scene 3, Shylock demands "a pound of fair flesh" from Antonio, but when time comes for Antonio to pay, Shylock is duped by Portia (dressed as a lawyer, Balthasar) who says that the "bond doth give thee here no jot of blood. The words expressly are 'a pound of flesh'." (Act IV Scene 1) Thus Antonio is saved by a technicality and his "Christian blood." All these blood ties and mentions seem to be the core life of the story. Blood runs throughout the plot forging ties between characters and situations and ultimately leads to the resolution of the play. How fascinating!

Throughout the play blood acts as a common recurring theme. This is very interesting to me. It appears that blood is an idea that connects people in this play. Shylock and Jessica are linked (this may be unfortunate in Jessica's mind) because, being his daughter she is Shylock's "own flesh and blood" (Act III Scene 1). In the same act, Shylock links himself to Christians by finding the common ground with the question "if you prick us do we not bleed?" The Moroccan prince claims to be as good a suitor as anyone else by offering to "prove whose blood is reddest" (Act II Scene 1). In Act I Scene 3, Shylock demands "a pound of fair flesh" from Antonio, but when time comes for Antonio to pay, Shylock is duped by Portia (dressed as a lawyer, Balthasar) who says that the "bond doth give thee here no jot of blood. The words expressly are 'a pound of flesh'." (Act IV Scene 1) Thus Antonio is saved by a technicality and his "Christian blood." All these blood ties and mentions seem to be the core life of the story. Blood runs throughout the plot forging ties between characters and situations and ultimately leads to the resolution of the play. How fascinating!

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

All That Glisters is Not Gold

This play is much more difficult for me to follow than the previous plays we have read. I feel like the play jumps around from scene to scene really rapidly making it a tad confusing. The blatant anti-Semitism that is seen in this play is a bit disarming, however it is still an interesting read. Shakespeare clearly went into this knowing that a Jew was seen as less than human at the time and used that as a jumping off point for the comedy effect. Knowing some background on the Jews in Englang at the time has been helpful in the justification of the Jewish slander involved in the Merchant of Venice. Shylock is portrayed as a horrible and kniving character and I personally dont care for him, however, I dont think that my dislike is based anything on his Jewish-ness. I can see how people could use it against him in the play though.

The other plot that includes Portia is interesting to me as well, she strikes me as a bored princess. The game used in gaining her hand seems to concern her very little. I am interested to see how the rest of this subplot is handled.

The other plot that includes Portia is interesting to me as well, she strikes me as a bored princess. The game used in gaining her hand seems to concern her very little. I am interested to see how the rest of this subplot is handled.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Ambiguity in Taming

It was really interesting in class today to have deeper discussion about Katherine's taming. I liked the idea that the play was based on a (silly and laughable) man's ideal. I like to think that the comedy came from Katherine's wit, intelligence, and sarcasm and not from the rituals that Petruccio uses for the "taming." I like to picture Katherine in complete control of the situation; but perhaps it is sadly true that she was brainwashed. The speculations about this play are really fascinating and I am glad that it is ambiguously open ended. Comedy has certainly changed a lot socially and culturally for us today; maybe not necessarily in a good way, but still the change makes it more difficult for us to understand exactly where Shakespeare is coming from. All the angles my classmates offered got me thinking about other alternatives and it is fun and frustrating all at the same time that there is no clear answer. But, I suppose, such is life.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

"tell these headstrong women what duty they do owe their lords"

In Act V Scene 2 Katherine displays the paradigm of the "tamed wife" in her final speech. She seems to have come a full one-eighty from the beginning of the play. Katherine now appears to live to serve "thy lord, thy king, thy governor." While these statements may seem near-blasphemy for the Katherine from Act I, I think there is victory for the shrew in the end as well.

Katherine's speech has always been in verse, but in the beginning of the play she spoke with a quick wit to say things like "asses are made to bear, and so are you." Now her poetry is smooth and docile, much like the ideal woman is believed to be by the men in the play. Strong feminists will ooze disappointment that Katherine now claims that "thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper, they head, thy sovereign." These are such womanly statements made by Katherine, who was so independent and outspoken in the beginning. People may attack this speech as being a disgrace to her earlier vents of defiance and independence; however, I do not see it this way. I am no supporter of being a passive and obedient woman. I believe that Katherine sought a voice; that she longed to be vouched for, to be listened to, and to be heeded. All that being said, in the end, Katherine gets her say. The floor is opened up for her to say what she will. I think she is happy with that freedom of voice. Maybe when someone gave her a chance, she said what she really wanted to say the whole time and it was completely unexpected. Or perhaps she said what Petruccio wanted to hear in gratitude of him giving her a chance to have her voice heard.

When she had everyone's full attention, I think that Katherine wished to share what she learned. In seeming the submissive and obedient wife, she got her voice and maybe even had a chance to share with the class what she ascertained from experience. In lines 174 to 180 Katherine admits to her pride by saying, "my mind hath been as big as one of yours" but then also admits that her pride and strong will did not get her very far, because people started to ignore her when she nagged. She points out that her efforts to rebel and be listened to were "but straws" and that in the end it was best to "vail your stomachs, for it is no boot." Katherine learned that she had more power in (the appearance of) obedience because then she had a voice to use. I think she was well aware that she would have to use it wisely and perhaps say what she wanted very subtly, but at least she was given the best gift, the gift of voice.

As we discussed in class, power resides in voice and I honestly believe that Katherine was not cheated and tricked into being tamed. I think she got exactly what she wanted even though it meant that the men got what they wanted as well. Shakespeare cleverly gives the woman the power in the end, and she used her power for the good of her husband. Although some may find it irksome that Petruccio got his way, is it always so bad to have a day without strife in a marriage? Especially if everyone wins.

Katherine's speech has always been in verse, but in the beginning of the play she spoke with a quick wit to say things like "asses are made to bear, and so are you." Now her poetry is smooth and docile, much like the ideal woman is believed to be by the men in the play. Strong feminists will ooze disappointment that Katherine now claims that "thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper, they head, thy sovereign." These are such womanly statements made by Katherine, who was so independent and outspoken in the beginning. People may attack this speech as being a disgrace to her earlier vents of defiance and independence; however, I do not see it this way. I am no supporter of being a passive and obedient woman. I believe that Katherine sought a voice; that she longed to be vouched for, to be listened to, and to be heeded. All that being said, in the end, Katherine gets her say. The floor is opened up for her to say what she will. I think she is happy with that freedom of voice. Maybe when someone gave her a chance, she said what she really wanted to say the whole time and it was completely unexpected. Or perhaps she said what Petruccio wanted to hear in gratitude of him giving her a chance to have her voice heard.

When she had everyone's full attention, I think that Katherine wished to share what she learned. In seeming the submissive and obedient wife, she got her voice and maybe even had a chance to share with the class what she ascertained from experience. In lines 174 to 180 Katherine admits to her pride by saying, "my mind hath been as big as one of yours" but then also admits that her pride and strong will did not get her very far, because people started to ignore her when she nagged. She points out that her efforts to rebel and be listened to were "but straws" and that in the end it was best to "vail your stomachs, for it is no boot." Katherine learned that she had more power in (the appearance of) obedience because then she had a voice to use. I think she was well aware that she would have to use it wisely and perhaps say what she wanted very subtly, but at least she was given the best gift, the gift of voice.

As we discussed in class, power resides in voice and I honestly believe that Katherine was not cheated and tricked into being tamed. I think she got exactly what she wanted even though it meant that the men got what they wanted as well. Shakespeare cleverly gives the woman the power in the end, and she used her power for the good of her husband. Although some may find it irksome that Petruccio got his way, is it always so bad to have a day without strife in a marriage? Especially if everyone wins.

A Disturbing Cruel Joke about a Beaten and Tortured Wife

"A Merry Jest of a Shrewd and Cursed Wife" made me want to hurl. I could of course see the connections between this poem and Taming of the Shrew, however this poem was much darker and disturbing to me. The play allowed some imagination of a humorous concept, no part of this poem struck me as funny. The parents set a horrible and sad example for their two daughters. There was no teamwork in that relationship, and while I understand that the concept of "team" probably didn't extend to matrimony, I saw only unhappiness there. I also found myself not appreciating the clear favoritism of Father and youngest daughter, and Mother with eldest. The father, who apparently is suffering from a wife who "would take him on the cheeke, or put him to other payne" feels strong dislike for his oldest daughter "and of her would fayne be rid." I hope any daughter reading this feels embarassed for this dad and perhaps a little nausea is fitting as well.

The marriage between the young man and the oldest daughter clearly will not have a good outcome. The father issues a warning about loving his shrew of a daughter, and oh by the way, don't piss off my wife. This message cannot forshadow good things. Instead of working things out like competent sharing adults, they beat each other up. It really concerns me that the first reaction of the couple is violence, much like Katherine and Petruccio. Was violence always an answer in early modern England? How were there functional families? Abuse is a horrible addictive chain that only breeds resentment and further violence. That is no environment to raise a familiy in. Furthermore, this "Jest" laughs at the fact that "with Byrchen roddes well beate shall she be." Not only is she beaten but her husband binds her "in Morels salte skin" to literally rub salt in her fresh wounds to torture her. This "taming" can only lead to more distrust and spawns fear and a life of acting to avoid pain.

The horribleness of this "Jest" makes my skin crawl because no matter how awful and nagging a woman may be, physical abuse can never, ever, ever be justified. Maybe it is easier for me to smile at the comedy in Taming of the Shrew because it is less graphically violent. I also feel that Katherine is given some voice, and I choose to believe she was tamed because she wanted to openly love someone, not because Petruccio beat it out of her. I am probably just delusional, but nonetheless I find it more difficult to tolerate "A Merry Jest" than The Taming of the Shrew.

The marriage between the young man and the oldest daughter clearly will not have a good outcome. The father issues a warning about loving his shrew of a daughter, and oh by the way, don't piss off my wife. This message cannot forshadow good things. Instead of working things out like competent sharing adults, they beat each other up. It really concerns me that the first reaction of the couple is violence, much like Katherine and Petruccio. Was violence always an answer in early modern England? How were there functional families? Abuse is a horrible addictive chain that only breeds resentment and further violence. That is no environment to raise a familiy in. Furthermore, this "Jest" laughs at the fact that "with Byrchen roddes well beate shall she be." Not only is she beaten but her husband binds her "in Morels salte skin" to literally rub salt in her fresh wounds to torture her. This "taming" can only lead to more distrust and spawns fear and a life of acting to avoid pain.

The horribleness of this "Jest" makes my skin crawl because no matter how awful and nagging a woman may be, physical abuse can never, ever, ever be justified. Maybe it is easier for me to smile at the comedy in Taming of the Shrew because it is less graphically violent. I also feel that Katherine is given some voice, and I choose to believe she was tamed because she wanted to openly love someone, not because Petruccio beat it out of her. I am probably just delusional, but nonetheless I find it more difficult to tolerate "A Merry Jest" than The Taming of the Shrew.

"Kiss Me Kate"

The cliched phrase quoted above has been used to haunt me and taunt me since I was four years old. I was unfortunate enough to share the name with "Kate" of Taming of the Shrew. I have many mixed feelings about the relationship between Katherine and Petruccio. For all intensive purposes of enjoying the text, I am glad that the two of them end up happily kissing the night away. However, I must admit that in this (my second reading of the play) my attention was drawn to harsh taming rituals performed to bend a woman -- specifically Katherine -- to a man's -- specifically Petruccio's -- will. There is all sorts of unfairness here, but of course times were different and humor and relationships were dealt with in ways entirely foreign to us millennials. I almost feel guilty for finding some instances humorous, and for being glad that Katherine ends up with a nicer disposition. I feel like I am not being enough of a feminist. But is it wrong for me to be happy and rejoice with Petruccio as he announces, "and being a winner, God give you good night." I am happy for the couple. Is that wrong? Should I worry more about the injustices Kate suffered? probably. Should I be concerned that Petruccio tortured her? probably. But can't I also see how Katherine was just being plain bitchy sometimes? definitely. Certainly there are issues here, but for the sake of literature, I am reveling in my pretense of seeing this as pure inane comedy.

Thursday, September 10, 2009

"Is it your will to make a stale of me amongst these mates?"

I find Katherine to be a really incredibly complex and interesting character. Is she just like every girl who is burdened by the "perfect younger sibling?" Or is she a violent character driven by an evil will? It is so hard to tell, but perhaps sometimes against my better judgment, I really really like Katherine and feel sympathy for her. I am such a headstrong loudmouth in my moments, and I cannot imagine being unable to voice anything. I get so offended when I am not being taken seriously. I love her display of witty banter and the connection she has with Petruccio even though he is a cocky (ahem), ridiculous display of masculinity. The clip of the movie we watched in class today was an interesting take on the first scene with Katherine and Petruccio. I can see how maybe she is a little pleased with the attention, but I really do think she is upset about being forced into a marriage. Petruccio twisted the scene around to make it seem like she wanted it in front of Baptista ("She hung about my neck, and kiss on kiss..."). That would make me SO angry; and it would be worse that no one believed me.

I hope to further understand Kate and I hope that she does not disappoint me in being "tamed."

I hope to further understand Kate and I hope that she does not disappoint me in being "tamed."

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

"action might become them better"

The last segment of the Rape of Lucrece contains many important elements to be considered. Lucrece speaks to opportunity, time, and shame. These things she blames for what happened to her. She wanted to feel more justified in her anger and questioned causes and reasons. She accused opportunity of letting Tarquin in and blames shame for making her feel honor-bound. And time she blames for existing and taking away youth and innocence. She then considers a painting of the war at Troy. Lucrece makes various connections with that battle scene and her own circumstance. She feels complete agony and bears all the burdens of the rape, which in her society would not be more socially harmful to her than her husband, Collatine. She likens herself to Hecuba, Priam's vife, the queen of Troy. In the painting she is ugly and painstricken in compassion for all the harm that has come to her dear husband. Lucrece sympathizes with this woman and speaks of how unfair it is that she has no voice. Shakespear may be toeing the line of what was culturally acceptable by showing sympathy to women in forced silence. Lucrece also likens "perjured Sinon" to Tarquin by noting how kind and well seeming he looks. There are endless connections between the painting and the rape. It is so fascinating to me the underlying cultural markers Shakespeare leaves.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

"For in thy bed I purpose to destroy thee"

The actual rape in this poem is a remarkable study of struggles between two people and the struggle within one's own mind. Tarquin knows undoubtedly that he should NOT rape Lucrece. Yet he does it anyway, even when she pleads with him, "thyself art mighty...myself a weakling" he does not change his course of action. Why? I don't understand! Surely reason would take over? He has countless times of consideration all coming to a negative end, "I have debated even in my soul/What wrong, what shame, what sorrow I shall breed." However he mangages to assure himself, "But nothing can affection's course control." Tarquin must be sick in his head. And Lucrece puts up a very small struggle (I have already expressed my problems with this) and succumbs to the rape feeling completely defiled and dirty.While it is disturbing (as any rape should be), this particular rape is so interesting because Shakespeare paints it to make it almost a little sympathetic to Tarquin because he has this internal conflict. The bad prevails to be sure, but the fact that this internal struggle even exists is really intriguing to me.

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

rape on the first day of class

today we got the assignment to read the beginning of The Rape of Lucrece. I got sucked in and read a ways into it. I also looked up a portrait of Lucrece...

I like the fight in her here...while I don't understand a fight if she ends up killing herself anyway, I still prefer the idea that she did not lay there like a helpless vegetable and take it. That sounds bad...I don't disagree with Shakespeare's description of the rape - I just wish she did not seem as if she had completely given up after verbal suggestions.

I like the fight in her here...while I don't understand a fight if she ends up killing herself anyway, I still prefer the idea that she did not lay there like a helpless vegetable and take it. That sounds bad...I don't disagree with Shakespeare's description of the rape - I just wish she did not seem as if she had completely given up after verbal suggestions.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)